Circumcision, Citizenship, and Grace in Acts 15 and Ephesians 2

Last week I was asked by our Bible study small group leader to teach our next study on Acts 15, which happens to revolve around the subject of circumcision. And while this might not be the most sought after topic for a modern-day 20s-30s Bible study group, this past week, as I have studied Acts 15:1-12, God has shown me not only how important of a cultural and religious issue circumcision was for the first-century Christian church, but also how modern-day political issues such as immigration can act as an analogy for us to understand the importance the circumcision debate held for early church leaders. Further, immigration and citizenship rhetoric become a scriptural metaphor used by St. Paul in his letter to the Ephesians, a connection point God only just illuminated for me during a recent small Bible study I held with my mother and father. This essay works as a written lecture for what I plan to share at my small group Bible study and hopefully helps to flesh out some of the ideas I’m still working through as I continue to ponder the records of the early Jesus movement in Acts.

Paul, Barnabas, and the Gentile Party in Acts 14:27-28

Before camping out in Acts 15:1-12, let’s make sure we understand the narrative context for our story. Paul (previously known as Saul, and a former Pharisee; more on them later in this essay) and Barnabas (a nickname the apostles gave him meaning “son of encouragement; his real name was Joseph[1]) are on fire for the Word, as they travel together through the ancient world of Asia Minor, bringing news of Jesus’ gospel to the nations, including the Gentiles, a Latinate word which means “belonging to a people.” As Chad Chambers notes, “The Hebrew and Greek words translated as Gentiles mean ‘people’ or ‘nations.’ Bible translations selectively use Gentiles to designate non-Jews.”[2] God’s conventual redemptive blessing is no longer confined to the line of Abraham and the twelve ancient tribes of Israel, for now God “had opened a door of faith to the Gentiles,” welcoming them into the fold of Christ’s family (Acts 14:27).[3]

What a wonderful image Acts 14 ends on! The “door of faith” was open to non-Judean people, an image invoking philoxenia (φιλοξενια), or hospitality, “The generous and gracious treatment of guests.”[4] Every Sunday, our 20s-30s Christian group get together at one of our friend’s townhouses, and weekly he demonstrates practically what philoxenia looks like in a Christian community. In fact, his philoxenia is so welcoming that his door is always unlocked, a running joke within the group, as literally anyone could walk into his house. And yet, that is exactly what the family of Christ is like now, for through Christ’s redemptive sacrifice, Jew (an ancient Judean practicing Judaism) and Gentile alike, according to the scriptures, can walk into God’s house and experience God’s spiritual philoxenia. God “had opened a door of faith to the Gentiles,” a beautiful phrase reserved only for the spiritual description of Gentiles who came into the Christian faith. We will return to that word faith, or pistis (πίστις) later in the essay.

Acts 14 ends with a joyous description of Paul and Barnabas among fellow believers in Antioch, the headquarters of the new Jesus movement in the first century, as “they remained no little time with the disciples” (Acts 14:28). If you spend “no little time,” that means you are spending a lot of time. And what do you think they were doing during all that time together? Rejoicing about “all that God had done with them” as Paul and Barnabas worked together to share the good news to the Gentiles (Acts 14:27). Acts 14 ends jubilantly, with images of smiles and joyous celebration permeating our imaginations. But then, a big “but” comes at the opening of Acts 15.

The First “But”: Acts 15:1-4

Acts 15:1 opens with a big “But.” In English grammar, “but” is a subordinating conjunction, a part of speech connecting words, phrases, or independent clauses which both hold equal grammatical (although not conceptual) weight. “But” in Acts 15:1 contrast what we see at the end of chapter fourteen with a problem, or conflict, introduced into the narrative at the opening to the next chapter.

Acts 15:1

But some men came down from Judea and were teaching the brothers, “Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved.”

Any good story needs a conflict, and a big “but” has just entered the scene. Just as things were picking up steam, an obstacle is introduced into the narrative which acts as a stumbling block for new Gentile believers in the early Jesus movement. And thus, the primary sociopolitical and religious issue at stake in Acts 15 is introduced: Do we have to be circumcised to be saved?

To understand the cultural weight of the circumcision issue, we must do a brief flashback into the first couple chapters of the Hebrew Bible. Circumcision as a physical medical process, whereby the foreskin of the penis is removed, was not unique to the ancient Israelites. As Kelly A. Whitcomb and Getachew Kiros note, “Although there is no concrete evidence that circumcision was practiced in Mesopotamia, it is attested elsewhere in the ancient Near East. The circumcision of male boys was a common practice among the Ammonites, the Moabites, the Edomites, and the Egyptians.”[5] Circumcision was probably a common ritualistic practice in the Ancient Near East, “with the exception of the Philistines.”[6] Where Israel differed from their geographical neighbors was in their symbolic significance of the referent. In what merits a rather long quotation, Michael S. Heiser explicates the emblematic implication of circumcision:

When God told Abraham to be circumcised, he was past the age of bearing children and his wife, Sarah, was incapable of having children (Gen 18:11). Nevertheless, it would be through Sarah’s womb (Gen 17:21; 18:14) that God would fulfill His promise of innumerable offspring to Abraham (Gen 12:1–3). God’s covenant with Abraham could only be realized by miraculous intervention.

The miraculous nature of Isaac’s birth is the key to understanding circumcision as the sign of the covenant. After God made His promise to Abraham, every male member of Abraham’s household was required to be circumcised (Gen 17:15–27). Every male—and every woman, since the males were all incapacitated for a time—knew that circumcision was connected to God’s promise. It probably didn’t make any sense, though, until Sarah became pregnant.

Everyone in Abraham’s household witnessed the miracle of Isaac’s birth. From that point on, every male understood why they had been circumcised: Their entire race—their very existence—began with a miraculous act of God. Every woman was reminded of this when she had sexual relations with her Israelite husband and when her sons were circumcised. Circumcision was a visible, continuous reminder that Israel owed its existence to Yahweh, who created them out of nothing.[7]

Circumcision came to represent Israel’s tribal creation story, as God brought life quite literally out of nothingness. Sarah, from a five senses and biological perspective, was incapable of bearing children, having passed her menopausal stage decades ago. And yet, through God’s miraculous workings, life was created in Sarah’s womb from Abraham’s seed. Circumcision was not just a ritualistic tradition which the ancient Israelites took part of; it was a critical symbol of cultural origination helping them remember by whose power they were brought into existence. However, notice Heiser never mentions a link between circumcision and salvation. As Craig S. Keener observes, Judaic teachings in the first century “required gentiles to be circumcised to join God’s people (a position different from Paul’s), but at least some Judeans (such as those depicted in 15:1) went further, demanding it even for salvation and table fellowship.”[8] This was a major issue for the early church because people’s belief in their path to salvation was being influenced by these zealous individuals. And I use the term “zealous” intentionally because of how Luke (the traditionally accepted author for Acts) introduces the “some men from Judea.”

We don’t know who these men were, as the only details we learn about them is their radical new doctrine of salvation through circumcision. I don’t think Luke is portraying them as inherently evil or malicious. By excluding their names (no doubt Paul and Barnabas knew who they were), Luke is emphasizing their words and characterizing these individuals as zealots, individuals who are “zealously, fervently or passionately devoted to a cause or belief, or to the pursuit of an objective or outcome. Frequently (and now usually) with disparaging implication: […] person[s] who [are] excessively, immoderately, or fanatically devoted to a cause or ideal, esp. a religious or political one.”[9] These “some men from Judea” are excessively devoted to the Mosaic law as outlined in the Torah, and, as Keener spelled out, these individuals are actually taking the meaning of the law a step further than its intention. However, Luke is not disparaging their personal character by attacking them by name, a subtle yet gentle narrative touch in this account.

Consider for a moment these men’s possible intention. I’d venture to guess they weren’t seeking to do spiritual harm in the new Gentile disciples’ lives; they did cause division within the early Jesus movement but isn’t that relatable in our Christian culture today? People (for the most part) are not actively seeking to speak evil into our lives. And yet, because of misdirected passion, or zeal, we can often be led astray from the path God would have for us.

There is also another sociopolitical subtext regarding the importance of circumcision for first century Jews, for as Keener brings out attention to, “By the mid-40s, in the wake of Caligula’s threats and Agrippa’s rule (cf. 12:3), Judea experienced a revival of nationalism, which influenced also the Jerusalem church.”[10] The Judeans were being oppressed by the Roman politicians and governing systems, so circumcision again took up a symbolic significance, this time representing sociopolitical protest against the Romans. Circumcision, as a sign, came to represent a plethora of religious, social, and political referents, which is why this issue was so contested. Spiritual and national identities were at stake.

There is also another cultural element we must recognize: the Greco-Roman perspective on circumcision. Both the Greeks and the Romans rejected the practice of circumcision, with many in their culture believing it to be a mutilation of the natural human form, denigrating the body’s beauty.[11] Hence, Greco-Roman culture “deride the custom as superstitious and depraved and portray it as an attempt to control sexual relations between Jews and Gentiles.”[12] This situation was exacerbated for Hellenistic Jews, individuals whose native culture and religious was Jewish but who lived in the Greek-speaking world. As Whitcomb and Kiros remind us,

male members of society participated in the gymnasium [stemming from the Greek gymnos (γυμνός) meaning naked; the educational center in Hellenistic culture[13]] where they practiced sports unclothed. Because the Greeks did not practice circumcision, those who were circumcised could be shunned socially. Hellenized Jews thus ceased the practice of circumcision so their sons could participate in the gymnasium without persecution.[14]

Hellenized Jews were between a rock and a hard place. Either circumcise and practice Judaism according to its sacred teachings but be ostracized and shunned by Greeks, or don’t circumcise and be rejected by their fellow Judaic worshippers but follow the social norms of their Greek culture. Appreciating the circumcision question from both the Jewish perspective and the Greco-Roman viewpoint allows us to better understand the nuanced complexities surrounding the issue at stake in Acts 15.

We also should remind ourselves, returning to the text in Acts 15:1, that these “some men” were not dismissing what Christ did for us. Rather, they were, in effect, saying “Jesus + circumcision = salvation.” But Paul and Barnabas, in the following verse, stand for the equation “Faith in Jesus + God’s grace = salvation.”

Acts 15:2

And after Paul and Barnabas had no small dissension and debate with them, Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and the elders about this question.

Paul was a former Pharisee (Phil. 3:5), a word stemming “from the Aramaic word פרשׁ (prsh), which means “to separate,” “divide,” or “distinguish.”[15] Essentially a far-right conservative traditional socioreligious separatist subgroup within Judaism, the Pharisees “developed a tradition of strict interpretation of the Mosaic law, developing an extensive set of oral extensions of the law designed to maintain religious identity and purity.”[16] Paul would have empathetically understood what these men were arguing for. But since his conversion on the road to Damacus, Paul has come to view God’s workings in a different light. And so, he and Barnabas had quite the theological disagreement with these men—it was “no small dissention and debate” between them. In fact, this was such a weighty disagreement that it merited them being “appointed” (tassō; τασσω) to go to Jerusalem, the capital city of Judaism within the region of Judea, which was approximately 250 miles away from Antioch, and where these “some men” were from.

Verse three briefly outlines Paul and Barnabas’ trek over to Jerusalem from Antioch, noting how they stopped in with the believers in Phoenicia and Samaria, a subtle callback to Philip planting the church in Samaria (Acts 8:5). The whole time Paul and Barnabas continue rejoicing over what God has done through them, “describing in detail the conversion of the Gentiles” which “brought great joy to all the brothers” (Acts 15:3). Interestingly, Ian Howard Marshall claims “Luke’s comment that this news brought great joy implies that the churches in question probably took the same attitude to circumcision as Paul.”[17] Paul and Barnabas continue the good vibes with their testimony of the gospel’s spreading into the fourth verse: “When they came to Jerusalem, they were welcomed by the church and the apostles and the elders, and they declared all that God had done with them” (Acts 15:4). However, just like we saw that conflicting conjunction in verse one, the big “but” comes back to introduce even more issues during the Jerusalem Council.

The Second “But”: Acts 15:5-12

Acts 15:5

But some believers who belonged to the party of the Pharisees rose up and said, “It is necessary to circumcise them and to order them to keep the law of Moses.”

This is the second time we hear this argument, the first from Acts 15:1. However, this time, it seems like there is a bit more aggression and zeal behind these pharisaical Christians. Whereas those “some men” in the first verse merely said “Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses,” the officials in Jerusalem order (parangellō, παραγγέλλω) the Gentiles to follow the Mosaic law. There is nuance to parangellō, as it is used many times in association with intimidation.[18] While I suggested a more sympathetic reading of “some men” from verse one, Luke’s use of parangellō suggests a more aggressive characterization for those religious leaders in Jerusalem. This aggressive assertion is based on ancient Jewish cultural and religious traditions which “required proselytes [converts] to obey the Torah; becoming part of God’s people meant obeying the rules that govern God’s people.”[19]

However, maybe a sympathetic reading like we had for verse one is also possible for these former Pharisees in verse five. Marshall reminds us there should be nothing surprising about the Pharisees’ former traditional mindsets carrying over after Jesus’ coming and sacrifice: “We probably underestimate what a colossal step it was for dyed-in-the-wool Jewish legalists to adopt a new way of thinking.”[20]

This clash of cultural and theological differences between the party on Paul and Barnabas’ side and the former Pharisees is realized in the following verses.

Acts 15:6-7a

The apostles and the elders were gathered together to consider this matter. And after there had been much debate […]

Notice Luke’s detail, that this issue brought forth not a little debate but “much debate,” mirroring the “no small dissention and debate” Paul and Barnabas had with the “some men from Judea” (Acts 15:2). While we do not have record of what Keener calls an “executive session”[21] and what Marshall terms “a general free-for-all,” [22] we can imagine the debate lasted a while, probably more than a few hours, if not a couple of days. But it is Peter’s speech which is the focal point of this section.[23]

Acts 15:7b-9

Peter stood up and said to them, “Brothers, you know that in the early days God made a choice among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe. And God, who knows the heart, bore witness to them, by giving them the Holy Spirit just as he did to us, and he made no distinction between us and them, having cleansed their hearts by faith.

Peter begins with a shared sense of kinship (“Brothers”), as he was of Jewish heritage, having helped found the church in Jerusalem, earning him the distinction of “‘apostle to the Jews.’”[24] He establishes his credibility for speaking by appealing to the evidence of God’s workings through him in the early days of the Jesus movement, alluding to the story of Cornelius, the Roman centurion—a Roman army officer in charge of 100 soldiers—as recounted in Acts 10:1-11:18.[25] While the former Pharisees knew about this event, they evidently did not want the Cornelius model to become the norm for new proselytes to the Christian faith. Peter appeals to God’s omniscience (“God who knows the heart”), reminding his audience there is no distinction between Jews nor Gentiles through the blood of Christ, as all who have come to the faith have now received God’s Holy Spirit, as Christ dwells within each believer. No doubt, Peter’s testimony regarding the abolition of distinction between people groups is another allusion, this time to Acts 10:9-15 and his vision of the clean and unclean animals and God’s voice telling him “‘What God has made clean, do not call common’” (Acts 10:15). Peter also includes an echo of “the circumcision of the heart” in his claim that God has “cleansed their hearts by faith,” a phrase recalling passages like Deuteronomy 10:16, 30:6, Jeremiah 4:4 and Romans 2:29.

It is here we begin seeing how Peter is arguing for and against circumcision; we just need to understand what kind of circumcision he stands for. Clearly, for Peter, “what mattered in God’s sight was the cleansing of the heart, and that outward legal observances, such as circumcision, were a matter of indifference.”[26] The circumcision of the heart, or the spiritual cutting away of the old man nature, is only possible through a faith in Christ, actualized through God’s grace. The individual’s faith, or pistis, which can equally be understood as trusting obedience,[27]comes to signify a belief in what Christ has done for each person’s life through his sacrificial innocent blood shed for the atonement of humanity’s fallen nature. Christ’s blood, once the individual comes to a faith in what the Son has done, cleanses, or circumcises, the heart as the believer takes on the mind of Christ.

Peter ends his speech with a challenging question for his opposing audience and subversive closing remarks, flipping expectations regarding how way pro-circumcisers conceptualized salvation.

Acts 15:10-11

Now, therefore, why are you putting God to the test by placing a yoke on the neck of the disciples that neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear? But we believe that we will be saved through the grace of the Lord Jesus, just as they will.

Peter directly confronts the executive session by throwing back to them the burden of the Mosaic law. According to Peter, believing circumcision is necessary for salvation is akin to placing God to the “test” (peirazō; πειράζω), a Greek word holding connotations of “making an attempt and trying, or of testing, examining, and putting to the test.”[28] While it would be a digression to expound on the test motif from God towards humans within scripture,[29] suffice it to say, God has the authority to test his creation, but his creation does not have the authority to test their Creator. Testing God is taken as a serious theological offense (Luke 4:12, Acts 5:9), and recalls Israel’s testing of God in the wilderness after their freedom from slavery in Egypt (Exod. 17:2; Num. 14:22, Duet. 6:16, Ps. 78:18, 41).[30] Marshall expounds on this idea, writing, “to seek to impose the law on the Gentiles was to test God, in the sense of questioning his judgment to see whether he really meant it and whether men might get away with doing something different.”[31]In short, the way the relationship between God and humans is set up prohibits humans from testing God, for that breaks the hierarchical structure inherent between Creator and created. Whether intentionally or otherwise, the pro-circumcision party tries usurping God’s just judgement into their own hands. Peter rebukes them for such judgement by reminding them that neither their forefathers nor themselves were able to bear the yoke of the Mosaic law. Thus, it is hypocrisy for them to expect the Gentiles to do that which not even they could do on their own without Christ.

Peter triumphally, yet lovingly, closes his speech by reminding the audience that they are “saved through grace of the Lord Jesus” or charis (χάρις), a Greek word conveying the meaning of “a gift of kindness and favor given to a person or persons.”[32] Christ gracefully opened the “door of faith” to the Gentiles. Individuals are saved not by any work on their own, but through Christ’s fulfillment of the law (Luke 24:44, Titus 3:5). Peter exhorts his hearers to believe they are saved through Christ’s grace “just as they [the Gentiles] will.” Peter ends his speech with boldness! No doubt, the former Pharisees were expecting Peter to say something like “The Gentiles will be saved through grace, just like us.” But Peter subverts expectations, effectively telling his pharisaical audience that they need to take a note out of the Gentile’s book in how to walk in the Christian faith. Peter’s rhetorical K.O. with his last statement had a powerful effect on his audience.

Acts 15:12

And all the assembly fell silent, and they listened to Barnabas and Paul as they related what signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles.

The room’s silence can be read in different ways, from respect for Peter’s words to a lack of solid argumentation refuting Peter’s case. Regardless of how we take it, the silence read in the account is felt in our seats now, for we have been reading for the past eleven verses about how critical the circumcision issue was in Acts’ cultural moment. And now, by God inspiring Peter in his speech, all those tensions and complexities melt away. In Peter’s final appearance in the New Testament, he has demonstrated that “Outward signs were nothing compared to God himself, and a symbol of relationship with God was nothing compared to its eschatological fulfillment.”[33] I love the detail Luke includes in the verse’s latter part, that Barnabas and Paul continued their testimony of God’s workings through them for the Gentiles, mirroring verses 14:27 and 15:3-4.

Having gone through an exegesis of Acts 15:1-12, I would like to turn to an analogy for the circumcision issue, which I believe communicates in our own modern sensibilities the emotional and political charge circumcision had for the first-century believers. Let us turn to immigration.

Immigration, Citizenship, and Ephesians 2

This whole week I was mentally searching for an appropriate analogy to use in my teaching at our small group to connect our modern imaginations with the circumcision issue. Immigration continually came to mind. My great-grandmother, Kalliope, immigrated to America from Greece in the early twentieth century, speaking no English but coming through Ellis Island legally, and working in a family business, contributing productively to her community. Life was not easy for her, but she was a hard worker, and raised three children: George, Steve, and Mary. George and Steve served their country in the military, seeing combat in the Vietnam War and Korean War respectively, while Mary was an integral part of the Etimos family dry-cleaning business in Astoria, Queens. After years of living in America, Kalliope was granted a court hearing for the judge to decide upon her naturalization status. Mary needed to accompany Kalliope into the courtroom and translate what the judge spoke, as Kalliope could speak only broken English, and needed Mary to speak on her behalf. As the judge was looking at my great-grandmother’s files, he asked her if her sons served in the United States military, to which she responded “nαί,” Greek for “yes.” The judge told her any mother willing to see her sons go off and defend America deserves to be awarded citizenship. And so, with the fall of his gavel, the judge showed favor, charis, or grace, on Kalliope.

Kalliope’s story is a part of my family history, and this past week, God has shown me that, as with many things in life, it is through grace that gifts are bestowed upon us, and not because of external workings we do on our own behalf. Kalliope could not go to war, and yet her sons fought for her and the American country on her behalf. While it would be a stretch to suggest a corollary between my grandfather and my great-uncle as analogously inhabiting a correlative positionality to Christ, I believe the thought fruitful for pondering God’s grace in our lives.

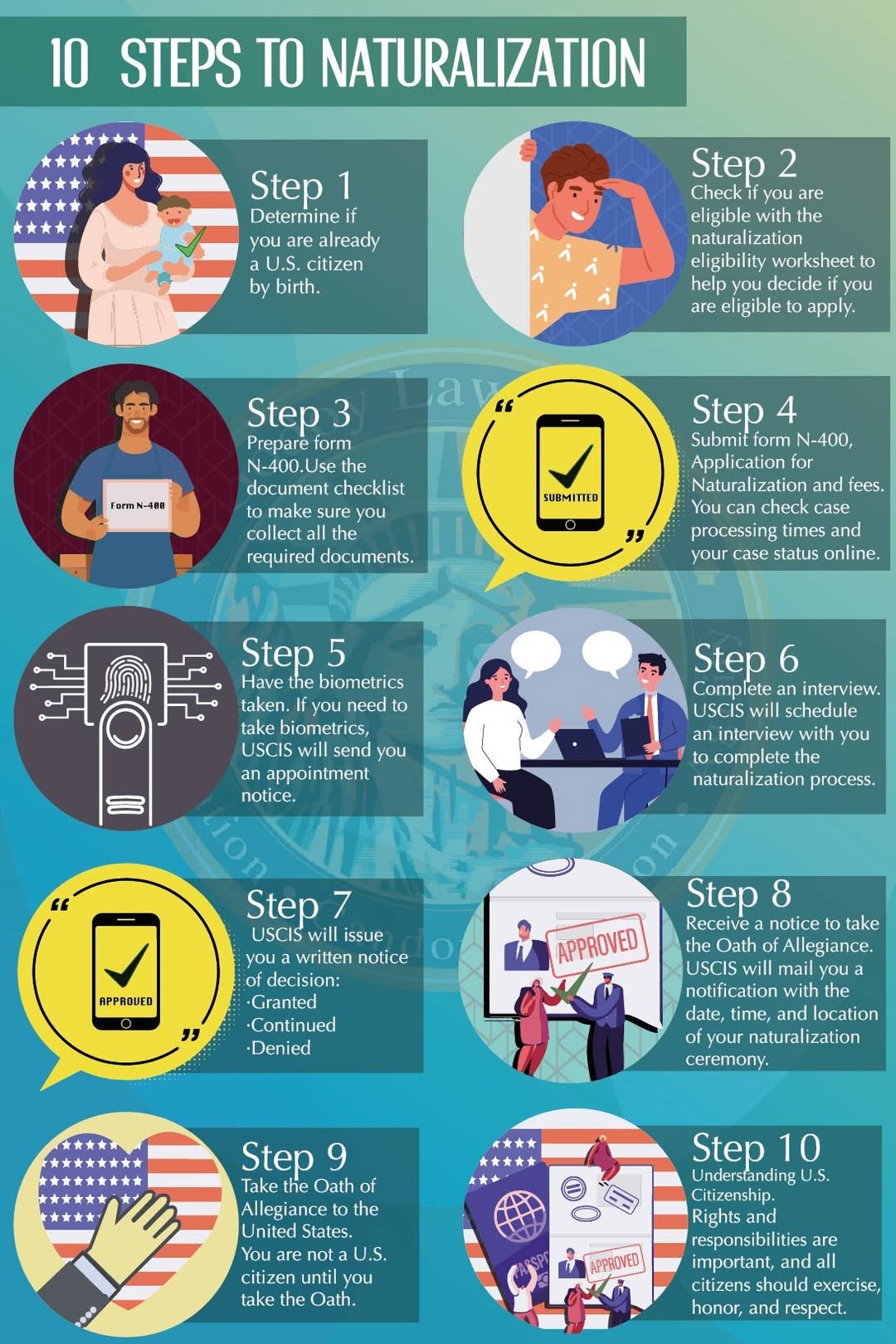

While Kalliope went through the naturalization process almost half a century ago, I think pondering our modern, twenty-first century immigration, green card, and naturalization processes also provide a thought-provoking mirror to the circumcision issue. Undoubtedly, immigration is one of the most pressing and hot-button topics in our modern sociopolitical discourse, and whatever thoughts you have on the issue, the fact remains that the path to citizenship for an immigrant to the United States is a burdensome legal process which at times can seem neigh near impossible. Look at the images below, the first showing a flow chart for perspective legal immigrants seeking entry into America, the second, another flow chart showing the process to earn a green card, and the third, the American naturalization process.

What stands out to me in the first image, showing the immigration process, is how the form physically looks like a computer circuit board! The complexities represented by the arrows, colors, flows, and countless questions would make anyone’s head spin like crazy. Also, notice how much more likely an individual is to land on a “DENIED” space (it’s like we are playing the game of “Life,” which I suppose for some people, they are), rather than the “MAY BE ELIGIBLE:” fourteen “DENIED” and eleven “MAY BE ELIGIBLE” spaces. And it’s not even a guarantee for legal immigration; it’s a maybe. Let’s just say an individual somehow miraculously and legally gets through the immigration process (because let’s be honest, becoming eligible based on that flow chart would be a miracle), the next step towards citizenship would be obtaining a green card. And the hellish game of “Life” starts all over again. Find what category you fit in (EB-1, EB-2, EB-3, EB-4, or EB-5), and follow the fateful questions, which will lead you either to seven possible “Sorry” spaces (a.k.a. denials) or six possible “Green Card” spaces. Again, even when applying for a green card, your chances of legal failure are more likely than legal success. And last comes the “10 Steps to Naturalization” poster, which looks a lot more inviting than the previous two flowcharts, as it should, seeing the tedious and exacting legal steps one has taken to get to this final stage. And even though the cartoons look more welcoming and cheerful, don’t let that fool you! These last steps towards naturalization can take years and cost tens of thousands of dollars, as individuals fill out and submit an “N-400” form (whatever that is), have a biometrics exam, complete an interview and successfully answer questions about United States civics and history that, if we’re honest, most American citizens can’t even answer. All these steps ultimately get approved or denied, granted grace (favor) or no grace (denial).

Now imagine a fictional situation where Kalliope and another woman (let’s name her Rachel) are in the same courtroom on the same day for their respective naturalization court appearances. On the left-hand side is Rachel, who has gone through the immigration, green card, and the naturalization processes, and has also expressed her allegiance and faith in the United States of America. On the right-hand side of the courtroom is Kalliope, whose file is significantly less heavy than Rachel’s because it doesn’t have nearly the amount of legal paperwork as Rachel’s. However, Kalliope, same as Rachel, professes her allegiance and faith in the United States of America. Both women are granted American citizenship, but how do you think Rachel feels? Bitter, resentful, and maybe even a little prideful, having gone through such a strenuous legal process? And how can this Greek, this Gentile, be granted the same rights as her? Rachel’s feelings are understandable, and if we are being honest with ourselves, true to the human condition. I know it might be tempting to read unsympathetically against the Pharisees in Acts 15, but their situation parallels Rachel’s, and would we be any different if we were in Rachel’s or the Pharisees’ shoes? And yet God wills “that all should reach repentance” (2 Peter 3:9) and “desires all people to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Timothy 2:4). But how does immigration and citizenship relate with Pauline rhetoric in Ephesians 2?

This weekend, during an intimate Bible study with my mother and father and running through my teaching for my upcoming small group, mom had a lightbulb switch on in her biblical memory as I was making the analogy between circumcision and immigration. She brought my attention to Ephesians 2:11-22. Paul writes of the Gentiles as “no longer strangers and aliens, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God” (Ephesians 2:19, emphasis added). Just like we use the term “illegal aliens” in our immigration discourse, Paul does too, just within a spiritual discourse. While the Gentiles weren’t called “illegal aliens,” they were referred to as “‘the uncircumcision’ by what is called the circumcision [Jews]” (Ephesians 2:11), a designation which made the Gentiles “alienated from the commonwealth of Israel and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world” (Ephesians 2:12, emphasis added). While commentators have made connections between Paul’s writing and the events in Acts 15 (specifically regarding Ephesians 2:15),[34] my mother observed Ephesians 2:11-22 represents an older, more mature Paul reflecting on experiences he had with the church earlier in his Christian walk, experiences like the Jerusalem council, where he did not have a lead role in the episode, subtly hinted at by Luke when he writes the council “listened to Barnabas and Paul” (Acts 15:12). Luke did not write “Paul and Barnabas,” as has been the customary style since Acts 13:43, a style reflecting Paul’s emergent leadership role in the early Jesus movement. But here, during the Jerusalem Council, Luke shows Paul taking a backseat, observing this momentous theological occasion. And it’s not until years later, while he is under Roman house arrest, does Paul reflect on the truths he witnessed in that executive session through his epistles. “For there is no respect of persons with God” (Romans 2:11).[35]

As I close this essay and get ready to go to our Sunday night small group, I am thankful to God for how He never ceases to supply blessings in our lives. For me, God’s blessing this week was having the time to dive into His Word in a nerdy, academic way. And yet, God knows that’s just how my brain works. But He also graced me with images, analogies, conversations, and questions over the past few days which I have faith will yield fruit not only in my life, but also in the lives of those I will see at small group tonight!

Notes

[1] Tresham, Aaron K. “Barnabas the Apostle.” The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry et al., Lexham Press, 2016.

[2] “Gentiles.” The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry et al., Lexham Press, 2016.

[3] Unless otherwise noted, the English Standard Version (ESV) translation is the edition cited for scriptural quotations.

[4] Wilson, Douglas K. “Hospitality.” The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry et al., Lexham Press, 2016.

[5] “Circumcision.” The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry et al., Lexham Press, 2016.

[6] Ibid.

[7] I Dare You Not to Bore Me with the Bible. Edited by John D. Barry and Rebecca Van Noord, Lexham Press; Bible Study Magazine, 2014, pp. 17–18.

[8] New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Acts. Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 359.

[9] “Zealot, N., Sense 3.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, September 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/4040169468.

[10] New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Acts. Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 359. See also Marshall, I. Howard. Acts: An Introduction and Commentary. InterVarsity Press, 1980, p. 263.

[11] Whitcomb, Kelly A., and Getachew Kiros. “Circumcision.” The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry et al., Lexham Press, 2016. See also Peter Schäfer, Judeophobia, Harvard University Press, 1998, p. 105.

[12] Ibid. See also Lawrence A. Hoffman, Covenant of Blood: Circumcision and Gender in Rabbinic Judaism, University of Chicago Press, 1996, p. 9.

[13] Edwards, W. T., Jr. “Gymnasium.” Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, edited by Chad Brand et al., Holman Bible Publishers, 2003, p. 694.

[14] Whitcomb, Kelly A., and Getachew Kiros. “Circumcision.” The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry et al., Lexham Press, 2016.

[15] Johnson, Bradley T. “Pharisees.” The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry et al., Lexham Press, 2016.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Acts: An Introduction and Commentary. InterVarsity Press, 1980, p. 263.

[18] Kittel, Gerhard, et al. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Abridged in One Volume, W.B. Eerdmans, 1985, p. 776.

[19] Keener, Craig S. New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Acts. Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 360. See also pp. 362-64 for a closer look at the circumcision issue in Acts 15.

[20] Acts: An Introduction and Commentary. InterVarsity Press, 1980, p. 263.

[21] New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Acts. Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 364.

[22] Acts: An Introduction and Commentary. InterVarsity Press, 1980, pp. 263–64.

[23] See Keener, Craig S. New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Acts. Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 365 for a consideration of the rhetorical structure of Peter’s speech.

[24] Cox, Steven L. “Peter.” Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, edited by Chad Brand et al., Holman Bible Publishers, 2003, p. 1282.

[25] For more on the Corneilus episode, see Woodall, David L. “Cornelius.” The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry et al., Lexham Press, 2016.

[26] Marshall, I. Howard. Acts: An Introduction and Commentary. InterVarsity Press, 1980, p. 264.

[27] Kittel, Gerhard, et al. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Abridged in One Volume, W.B. Eerdmans, 1985, p. 849.

[28] Kim, Sun Hee. “Testing.” Lexham Theological Wordbook, edited by Douglas Mangum et al., Lexham Press, 2014.

[29] See The Bible Project’s theme study of “The Test” here.

[30] See Keener, Craig S. New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Acts. Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 365.

[31] Acts: An Introduction and Commentary. InterVarsity Press, 1980, p. 264.

[32] Mathews, Joshua G. “Blessing.” Lexham Theological Wordbook, edited by Douglas Mangum et al., Lexham Press, 2014.

[33] Keener, Craig S. New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Acts. Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 363.

[34] Foulkes, Francis. Ephesians: An Introduction and Commentary. InterVarsity Press, 1989, p. 90.

[35] The Holy Bible: King James Version. Electronic Edition of the 1900 Authorized Version., Logos Research Systems, Inc., 2009, p. Ro 2:11.